- Home

- Bruce Eric Kaplan

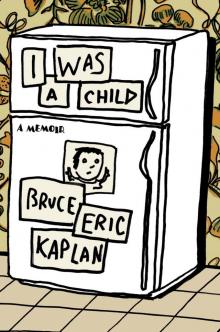

I Was a Child Page 6

I Was a Child Read online

Page 6

She brought the library book she was reading by Sue Miller to the hospital and it just sat there day after day. She never finished it.

One night I watched Something to Talk About with her because she wanted to. I couldn’t even follow it. I still have no idea what was going on in that movie.

Whenever I think of my mother, I think first of that five-week period she was at Saint Barnabas, then I try to remember who she was before that period, for my entire thirty-four years, but it is hard.

I still wish she got to finish the Sue Miller book.

• • •

THE KITCHEN CLOCK broke sometime after my mother died. My father replaced it with a drawing of fruit. For the next decade and a half, every single time I went into the kitchen, I always looked at that drawing of fruit to see what time it was.

• • •

MY FATHER was lost when my mother passed away.

• • •

ABOUT a year later, I was visiting him and opened the trunk of his car and found a pile of self-help books he had taken out of the library.

I looked at him. “Is there something you want to tell me?” I said, excited that he might want to meet a widower. He explained he was thinking about writing a book for widows from the male perspective.

Almost immediately after my mother died, my father threw himself into bereavement groups, making plans with friends, and dating. He met and fell in love with a woman named Flo. They never moved in together or married. They dated, seeing each other several times a week. My father was happy in a way I had never seen him be with my mother. Once he excitedly told me about something he and Flo had done. They went to dinner with another couple and had gotten two desserts and four forks for everyone to share them.

“Yeah,” I said. “Everyone does that.”

• • •

MY FATHER started to find his house a burden. He spent endless hours thinking and talking about moving, but never did. The house fell into disrepair, not that it had ever really been in repair.

I visited him once and when I walked up his block, coming from the train station, I noticed the houses had fresh coats of paint, and all looked exactly as they had when I was younger. But the people who lived there were different. There was evidence of young children all around. Except at my father’s house, which was originally a tan color, but that had now become gray. The gray, formerly tan, paint was peeling in places. My father was now Mrs. Soskin.

• • •

MY FATHER got prostate cancer and managed it for years. He got one protocol, then another then another.

What really seemed to bother him were his feet. He had a mysterious ailment with no treatment. Some days he would visit you with a cane, and some days he wouldn’t. He could only wear enormous white sneakers.

I remember looking at him, up at the Torah at my second cousin’s bar mitzvah, wearing his big white sneakers and thinking, He looks bizarre.

• • •

ONE DAY I called my father and found he hadn’t left the house for days. In fact, he had been sleeping on the couch because he couldn’t walk upstairs. I called my brother and we decided my father had to be forced to go to the emergency room.

Michael took him, and the doctor found out my father had fallen and broken his femur. When they operated they discovered he had bone cancer everywhere and had only six months to a year to live.

From the hospital, he had to go to a rehab facility in Plainfield, New Jersey. It was a bleak place and he was there for months, even though he clearly couldn’t be rehabilitated in any way.

My father was depressed. Flo asked Michael to get my father’s CD player clock radio and bring it to his room so he could at least listen to the classical music CDs he loved. He did, and at the end of the evening, he went to leave and my father told him to take the CD player clock radio with him. Michael said it was for him to listen to from now on. “You can’t leave it here,” he snapped. “What if the thieves take it?”

• • •

I NEVER drove so much on the New Jersey Turnpike. First going to the hospital, then the rehab facility, then finally, Flo’s house down by the shore, where my father lay in a hospital bed in her bedroom, tended to by a caretaker.

“Stay” by Rihanna was always on, especially if you were constantly switching between all the radio stations looking for it, as I was. I must have heard it hundreds of times on my drives down and back.

Now when I hear “Stay” it always reminds me of that time. I picture the mysterious smokestacks that line the highways of New Jersey. When I was a kid, I thought anything could be happening in those factories, and I still do.

That long spring, I would sing “I want you to stay” back to Rihanna at the top of my lungs. It is only now, a year later, that I realize I was probably singing it to my father.

• • •

BOTH MY PARENTS clung to life at the end. As their bodies began to decompose, they resolutely refused to go. It was horrible to watch, yet in a way, it was amazing. I had never seen either of them fight for something before.

• • •

ONCE MY FATHER was at Flo’s, he just lay in a bed.

Even though he could go outside, he had no desire to. I would sit in Flo’s bedroom, looking at the lawn chairs in her yard, wondering why he didn’t want to feel the sun on his face.

• • •

AT FLO’S, he never once mentioned the house he had lived in for so many years, and which he knew he would never go back to. I was stunned that he had no interest in talking about getting rid of his things—about who should get what, about what to throw out.

I kept thinking, He has this time here at the end and could have some kind of purpose. Why doesn’t he want to be in charge of getting rid of all his things? He could go through everything he had accumulated over the years and let it go. It seemed like a very profound opportunity. But he wasn’t interested.

I couldn’t understand it. Ever since I was little, I have always made sure to do one thing—clean up my mess. Nothing gives me more pleasure than putting things back to how they were.

I have always wanted to get rid of all traces of my being here.

• • •

THE LAST TIME I saw my father’s house, I noticed a hardened rag hanging from his bedroom window up above the front door. I wondered why he put that rag there—probably to solve some problem that putting the rag there didn’t really solve.

• • •

FOR SOME REASON I didn’t understand, we sold my father’s house weeks before he died. I was on my way to Flo’s but stopped off at my father’s house because we were all supposed to take anything we wanted.

I was in a state of shock about what was happening. I remember standing in the attic, frozen, not only unable to figure out what to take but unable to have a thought. It was such a strange, unfamiliar feeling to not be able to have a thought.

I stood there forever.

Then I just grabbed my It’s a Small World album and left the house for the last time.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

BRUCE ERIC KAPLAN, also known as BEK, is an American artist whose single-panel cartoons frequently appear in The New Yorker. He also has a whole other life as a television writer and producer.

Looking for more?

Visit Penguin.com for more about this author and a complete list of their books.

Discover your next great read!

filter: grayscale(100%); " class="sharethis-inline-share-buttons">share

I Was a Child

I Was a Child